It begins with an image of two hands meeting in the middle of an empty frame, creating an embrace. An embrace, as in the simple act of embracing another; be it another human being, as is the recognisable representation on screen, or more fittingly perhaps, another way of thinking. In this sense, the gesture becomes, at its most basic, a show of solidarity between two individuals, offering the viewer the perfect visual illustration of the collective spirit. A unification of a kind of shared ideology or ideal that offers an immediate contrast to what will eventually become a narrative preoccupied with disparities, ruptures and disagreements; as characters attempting to bring about a collective goal find themselves at odds with the generally accepted way of thinking.

As a creative statement, La chinoise (1967) can be seen as a direct response from Godard to the growing political consensus of the time; predating the eventual chaos of the Paris riots of May 1968 by almost a full year, but also successfully addressing the fact that a change is necessary, if not essential.

Although the film could be categorised (in the most generic sense of the term) a political film, La chinoise is really, at its core, a character study. In essence; a brisk social satire on the relationship between a group of young, bourgeois-minded revolutionaries, playing terrorists from the comfort a suburban apartment building owned by one of the group's parents. Throughout the film, Godard uses this basic narrative framework to explore the relevant ideas of the time, creating a film that could be seen as a sort of infernal parody of Dostoevsky's The Possessed (1872), in the sense that it creates a certain hermetic environment where the five central characters can ruminate on everything from nihilism, to conservatism, to utopias and utilitarianism - always maintaining that the discussions are only interesting because they reveal something more substantial about the characters, their motivations or the relationships within the group, etc - which continually cross back and forth, traversing the political line and into the personal.

In adapting something that at times seems closer to a theatrical presentation, in which a small group of characters address the various topics of discussion - either as a group, or directly to the audience - Godard is able to make the notion of the political commentary far more explicitly than if it were woven into a more conventional narrative framework. Instead, like the directly preceding Two or Three Things I Know About Her (2 ou 3 choses que je sais d'elle, 1967) or Masculin féminin (1966), Godard uses the basic form of the picture to blur the line between a documentary film and a work of fiction. Here, the varying layers of opinion - from characters that are real or adapted from reality, or from characters that are entirely made up - is carefully integrated in an attempt to present both sides of a potential argument.

This notion, of fictional characters interacting with real life, expressing their opinions on actual current events while at the same time acknowledging their own artificiality as creations in a work of fiction, is something that Godard would continue to refine throughout his career; eventually reaching a point with films like For Ever Mozart (1997) and Notre musique (Our Music, 2004), where the the line between layers becomes completely obscured.

Like the first film of Godard's '67 trio, the domestic satire Two or Three Things I Know About Her, La chinoise is effectively structured around a series of dialogues and sketches that establish the political climate of the period, the nature of these characters and their various relationships with one another, and finally their all encompassing views and opinions on concepts such as Maoism, the war in Vietnam and their particular position as Marxist-Leninists. In the past, many critics and audiences have misinterpreted the film as being Godard's ode to Maoism; working almost exclusively as a piece of socio-political propaganda in a similar way to how the influence of Marx is sometimes wrongly interpreted on the thematic foundation of the subsequent Week End (1967). However, it seems unlikely that Godard was being entirely celebratory with his depiction of a self-appointed student commune tackling the issues of the day in a series of ridiculous role-playing games, forthright discussions and the eventual urge for violence and revolution, but rather, using this absurd and provocative notion as a springboard to a series of more interesting discussions and routines.

As a result, attempting to explain the deeper subtext of La chinoise in any kind of greater detail can be a daunting task. After all, who is to say what Godard was really attempting to communicate with the film beyond what is immediately stated? As ever, we can only approach it on a personal level, by making assumptions and describing the experience first-hand. Though the ultimate intent of Godard, the political background of the film and the satirical nature of the presentation can all be seen as off-putting to those disconnected, either geographically or generationally from the events of this period, the basic foundations of the film and the dynamics between the four or five central characters is immediately recognisable. Though it is argued that Godard had a great belief in the ideologies of Mao and the teachings of his "little red book", he nonetheless argues against the beliefs of these central characters, either through the use of other, more informed supporting figures who voice their legitimate, real-life opinion from the fictional framework of the film, or through the actual structure of the picture; reminding the audience that these characters, although well-read and university educated, are still children, and thus, express themselves through childish games and fancy dress.

As withWeek End, the ultimate depiction of the characters here is often so contemptuous that we can only see it as underlining Godard's satirical intentions; as these opinionated young people bleat and pontificate amidst the director's onslaught of ironic visual motifs that seem to conspire to make a mockery out of their objectives and ideals. However, while Godard questions the intentions of his characters, celebrating their vigour and enthusiasm while simultaneously chastising their commitment and approach, the actual characterisation of the performers ensure that the presentation never turns in to caricature or farce.

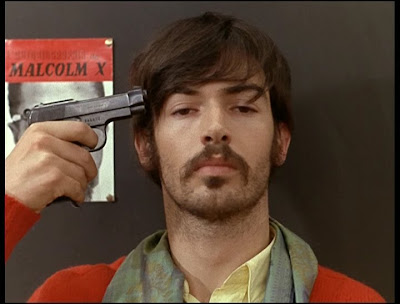

Throughout the film, these characters - although stylised and often speaking dialog that works as a kind of call and response argument - are completely believable, and it is to the often overlooked credit of Godard as a director of actors that these individuals register as just that; each a single character, clashing against an idea or ideal that is represented by the other, attempting to govern a collective utopia, but each being too selfish or too impatient for such dreams to ever be fulfilled. Here, the film benefits greatly from the lead performance of the young actor Jean-Pierre Léaud as the drama student Guillaume, whose playful pretension and look-at-me sense of theatricality make him an obvious and charismatic leader for the group, which also includes Anne Wiazemsky as would-be philosopher Veronique, Juliet Berto as a character reminiscent of a younger incarnation of Marina Vlady's character in "2 or 3 Things" (due largely to her farm-girl roots and casual prostitution) and Michel Séméniako as the conflicted and ultimately far more thoughtful of the group, Henri.

The way that these characters clash and contrast, brought down by their own personal relationships in the usual Godardian form of "couples" (e.g. both the relationship between men and women, and the more obvious coupling of sound as applied to image) further illustrates that this is a character study, and not simply a "political film". Even during the key scene, in which Veronique discusses the current cultural situation with the real-life philosopher and radical thinker Francis Jeanson - who criticises the actions of the group as childish and uninformed in a way that adds weight to the film's counter argument and to Godard's own potential perspective on his characters - the discussion is still important on the personal level, in what it reveals about Veronique as an individual. That this discussion takes place on a train, itself always moving in one direction, progressing, is incredibly apt; Veronique and Jeanson may be heading in the same direction, but they will never arrive at the same destination, not unless they can work together to form the correct course of action in place of this opposing adolescent folly.

From the very beginning, Godard defines La chinoise as a work in progress; something that is in the process of being made, always in motion, organic and alive with ideas. The familiar self-reflexive, deconstructive notion of fictional characters being treated to their own documentary feature, again, like Masculin féminin or Two or Three Things I Know About Her. The appearance of clapper boards, microphones and even the film camera itself skew the recognisable position between fiction and documentary; how can we be watching the film if the film itself is still being made?

It conveys that aspect of confusion apparent in the punning title, rife with double meanings. On the most obvious level, it is a reference to the Chinese Cultural Revolution of 1966, introducing the theme of politically-minded young people ready to heed the advice of Chairman Mao in the pursuit of the Communist ideal. However, in French, "Chinoise" can also refer to a kind of nonsense; "chinoiserie" = "an unnecessary complication" or "c'est du chinois" = "it's all Greek to me"; a lead-off from the scene in Made in U.S.A.(1966) in which Anna Karina slants her eyes, looks into the camera and confesses a state of confusion.

La chinoise is generally characteristic of Godard's shift into more radical forms of filmmaking beginning around the time of Pierrot le fou (1965) but really becoming more focused throughout 1966 and 1967; the pivotal period, pre-fin de cinema, during which the filmmaker released three completely different though no less radical features back to back. Even so, the familiar Godardian-look is still present; the use of inter-titles to offer commentary on the image and sometimes beyond it, here stencilled onto the walls of the apartment as well as intercut in the style of silent cinema; the incredible use of bold primary colours, like Le mépris (Contempt, 1963) or Une femme est une femme (A Woman is A Woman, 1961); the use of music, song and dance, of characters playing a role, poor Napoleon in his Theatre Year Zero; the extraordinary use of sound and shot composition. The pop-cultural references alongside literary quotations, highbrow and lowbrow, Marvel Comic superheroes and hand-coloured news clippings; ironic pop songs, masks and toys; in every scene the film is a perfect example of how to create an interesting frame on a limited budget as well as underlining the personalities of these characters, their approach to the situations and the greater political context that lurks on the edges of the drama.

Though mostly a playful film in tone, La chinoise hints at an escalating air of violence and political unrest, both in the cultural sense and in the sense of Godard's career as a whole; a violence that would eventually explode in the final moments of the apocalyptic Week End; in which car-crashes and the deliberate annihilation of literary creations places society on a road to inevitable destruction, and where the differences between cannibalism and consumerism are not that far removed. From here, films like One Plus One (1968) andLe Gai savoir (The Joy of Learning, 1968) would continue the formal experimentation, but would also make the political aspect more direct and the characterisation deliberately unclear. Conversely, a film like La chinoise seems perfectly structured around these individuals, so that the political commentary feels genuine, essentially because its coming from the characters and creating the drama, as opposed getting in the way of it.

Schalcken the Painter (1979)

Schalcken the Painter [Schalcken the Painter [Leslie Megahey, 1979]: This is a film I first saw around four years ago. At the time I found...

-

Schalcken the Painter [Schalcken the Painter [Leslie Megahey, 1979]: This is a film I first saw around four years ago. At the time I found...

-

In discussing the brief snippet from the ever contentious Uwe Boll's no-doubt harrowing new film Auschwitz (2011) - particularly the way...

-

The Image of Happiness or: 'the black leader' "The first image he told me about was of three children on a road in Icel...