An ephemeral landscape, always changing; the light, glowing, as statues living as monuments to the perseverance of the human spirit, chip away at the image of the past in the restless pursuit of industrial progression and financial gain. Never asking why, or stopping for a second to take in the sights, to savour the still life that suspends them in air like the tightrope walker in the film's final scene; who stands above the narrative, detached from it, watching like the alien anthropologists that descend in their spacecraft to link these two disparate characters across disconnected planes of time and space.

The observer: the watchful gaze of the camera as a surrogate eye, both impressionist and documentarian, conveying the real, as it is, as it happens, and yet abstracting, fragmenting; discovering new ways of looking at old things in order to glean some indecipherable meaning from within them. "Without them?": the question that hangs over these characters; the shifting thoughts and desires, the subjects and compulsions; which drives the urge to make right what was previously wrong? These are the spectres that lead our characters into this world of manmade ruin, where the filmmaker finds drama in its crumbled walls, decayed vestiges and half-sunken residences that peak, fleetingly, as if gasping for one final breath of air from the fierce flow of a rolling river, which, soon enough, will submerge these once-mighty relics, cementing them in time.

The film's opening sequence establishes a tone and an atmosphere that will develop throughout; a scene of quiet reflection on the Yangtze River, introducing us to the pensive coalminer Han Sanming on a boat bound for the Three Gorges region of the rapidly dissipating town of Fengjie. Here we begin the exploration of director Jia Zhangke's quietly compelling Still Life (Sānxiá Hăorén, 2006); an extraordinary work of enormous atmosphere and great natural beauty, about characters disconnected; in search of the past in a town in which the past is literally being levelled to make way for the future, and where the people we meet on life's lonesome journey fail to alleviate our struggle, acting only as markers; like the inanimate objects that we leave in our wake that remind people that we were here, that we existed.

Through this entrancing scenario, Zhangke is able to comment on the fleeting nature of time and existence; of the co-existence of two completely different characters arriving in this location at the same time and for similar reasons, though never once interacting. The symbol of the town and how these characters adapt to it also allows the filmmaker to form a more pointed commentary on the politics of contemporary China; in particular the sense of corruption and resulting violence that has been allowed to escalate and eventually destroy these grand historical settlements that have been inhabited, visited and documented in countless works of art and literature for many centuries past.

In this sense, it is a film of ever shifting perspectives; not simply in the emphasis on two separate characters, but in the specific way in which Zhangke is able to move so seamlessly between the poetic and the political, the abstract and the natural, so that the film feels like a kind of restless combination of Andrei Tarkovsky's great masterpiece Nostalgia (Nostalghia, 1983), in which a homesick Russian poet explores an ancient Italian village that holds the secrets to a haunted past, and Michelangelo Antonioni's unsung documentary film China (Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972), which recalls the notion of a film crew entering forgotten pockets of reality and creating a contemporary portrait of the world as it is (as it existed) at that point in time.

The thematic associations to these films - which are concerned, primarily, with the notions of memory and place - remind us of the longing, yearning melancholy of these characters and their own situations. Where each pensive look and glance beyond the landscape, at these human beings that exist on the periphery of the narrative, amidst a world that moves to the syncopated rhythms of sledge-hammers on stone, establish the psychological motivations that force these same protagonists to cling to what might ordinarily be seen as the insignificant leftovers of lives previously made vacant.

As the worn and weary bodies of demolition teams, dripping sweat and over exhaustion, set about deconstructing the final remaining signs of life from this fast-becoming ghost town, Zhangke is able to use these same allusions to the films of Tarkovsky and Antonioni to express the significance of this place, Fengjie, as a representation for something greater in scale; where the physical (as in, the physicality of the human body in contrast with physical embodiment of the place itself) meets the political, this world of capitalism and corruption. These themes are perfectly established in the film's early sequences, following Han Sanming's arrival at Fengjie and his initial interactions with its inhabitants.

As the character wanders off the boat and out amongst the throng of tourists and travelling workmen he is immediately coerced into attending a backroom magic show. Here, the "magician" promises to turn blank paper into cash, but only by fleecing the pockets of his unsuspecting audience. The scene is important for three reasons; firstly, in establishing the world of Fengjie and the borderline illegal activities taking place behind closed doors. Secondly, in further defining the determination of the character of Han Sanming, who, when faced with the threat of having his possessions stolen by the organiser of this group, watches, waits, then quietly pulls a flick-knife as the scene cuts to black. Finally, in introducing the character of Brother Mark (Zhou Lin); a periphery figure who befriends Han Sanming and enlivens him with his wide-eyed enthusiasm and John Woo posturing, becoming, in a sense, the presentable face of "young China" personified: dirty-dealing, underhanded, erring on the wrong side of criminality, and yet honest, genuine, good-hearted and kind.

There are a number of scenes throughout the film that continue this thread of the corrupt, capitalist society as a microcosm of contemporary China; an idea perhaps most apparent in the presentation of the character of Guo Bing (Li Zhu Bing). Here, or at least within the film's earlier scenes, Guo Bing becomes an almost metaphorical presentation; an enigmatic mystery at the heart of both strands of the film's narrative who will only become a true, fully-formed character, in the traditional sense of the word, when he is located by his wife Shen Hong (Zhao Tao) in the second part of the film.

The eventual meeting between Shen Hong and her elusive husband leads us, for the first time, to the dam itself; the great divide between them, as well as a symbol for the future of all concerned.

By focusing specifically on two separate characters (though with a clear emphasis placed on the first), the film allows Zhangke to look at both the complexities of human relationships and the transient nature of our existence. As a character, Han Sanming begins the film as a void; unable or unwilling to interact with his surroundings or these people seemingly beyond his understanding. As a character, he fits perfectly into the tradition of characters from previous Zhangke films - such as Bin Bin (Zhao Wei Wei) from Unknown Pleasures (Ren xiao yao, 2002) or Qun (Wang Yiqun) from The World (Shìjiè, 2004) - in the sense that, despite his apparent reservations or inarticulate nature, he ultimate proves himself to be entirely committed to his quest for answers and understanding; entering this condemned city and forging friendships and relationships that we believe in completely.

The film is also interesting in the way in which it grants the audience an outsider's perspective on this place - the Fengjie as it exists (or did exist) in 2006 - where the definitions of reality have become the stuff of science-fiction; an incredible notion illustrated by a rogue UFO or a bizarre piece of architecture uprooting itself and ascending to the heavens. Zhangke describes these moments as "an allegory of happiness: as elusive as their [the characters'] dreams of benefiting from these great changes" He explains; "I think the UFO and other special-effects shots are an extension of what I did in The World. With the speeding up of the transformation process, especially in the last two years, the main aspects of Chinese life have become absurd, surreal."

We can see this ideology and its obvious juxtapositions throughout the film, with Zhangke attempting to show the reality of the situation with the uncomplicated, unaffected DV images of cinematographer Lik Wai Yu, which capture without commentary and yet, in attempting to show the world in all its naked truth and harsh actuality, can only succeed in turning the natural vérité of life into something incredibly abstract or weird. It is an amazing contrast defined by the director himself as "the mixture of the ancient and the modern, the ethereal and the physical"; a philosophy that helps to transform the film into a kind of eerie travelogue of images and ideas developed around the themes of displacement and dislocation.

Here, the particular emphasis on the landscape and the exterior space that defines these characters' internal struggle - combined with the probing, existentialist questions that lead them to coalesce in this vanishing town in the restive pursuit of answers - creates an atmosphere and evocation of a certain time and place that is entirely tangible, if no less unreal. In this sense, the film becomes a quest for the soul to be reunited with the body (or vice versa); or for the ghosts of the past to be laid to rest, buried alongside centuries of survival in this town destroyed by greed.

It is telling that both central characters from Still Life have travelled to Fengjie from their home province of Shanxi; the hometown of Zhangke and the setting of many of his films, notably his debut picture, The Pickpocket (Xiao Wu, 1997). In the first thematic strand of the film, Han Sanming arrives in Fengjie to trace the wife and daughter that abandoned him sixteen years earlier. Through his investigation we learn the circumstances of their relationship; that she was a mail-order bride, unhappy with her situation, who took the opportunity to leave and never look back, and who now must face the questions and accusations of a man - who in all fairness was as much an innocent as she herself - attempting to find a teenage daughter (his own mark on this tragic still life) perhaps unaware of her father's existence. In the second thread of the narrative we're introduced to the character Shen Hong, a nurse, also from Shanxi, this time looking for her husband. Initially, it seems that Shen Hong is also looking for some kind of reconciliation; that like Han Sanming, she too has been wronged by a former lover and is looking for answers to the questions that have been such a burden during her husband's two year absence. However, as she likewise wanders this vanishing town - enlisting the help of an archaeologist, Wang Dongming (Hongwei Wang), a fitting compatriot for a character literally unearthing the secrets of the past in search of answers - we realise that her reasons for entering Fengjie are somewhat more selfish, and indeed, more befitting the commentary on the contemporary China that Zhangke is slowly moving towards.

The character Wang Dongming is another of these "periphery figures", an archaeologist who spends his days sifting through the reminders of the past - again, like the two central characters - and who lives in an apartment in which the notion of time has become a literal line traced along the wall of his living room.

Though the English translation of the title, "Still Life", does well to establish one of the main threads of interpretation that is explored throughout - chiefly, the central theme of existence and a search for the past - it is the literal translation of the title from the original Mandarin, Sānxiá Hăorén, or "The Good People of the Three Gorges", which really underlines the broader, socio-political aspect of Zhangke's creative and thematic intentions. However, the film could have easily have been called 'A Place on Earth', with full reference to Jean-Luc Godard's esoteric drama "Keep Your Right Up" (Soigne ta droite, ou une place sur la terre, 1987); another great film about the struggle of existence that places the emphasis on the act of creation (or in this instance, destruction); as characters search for someone or something to belong to (a place of their own, be it physical or metaphorical). Godard described his own film as "a two-way travel between sky and earth, between comic and experimental, between shadow and light", and although the term comic should (in this instance at least) be replaced by the more applicable term "cosmic", the description could just as easily apply to the film of Zhangke. It is within this contrast between shadow and light, between the sky and the earth and more importantly between (the image of) man and the landscape (again, the central theme of the aforementioned Antonioni) that the power and the beauty of Still Life is eventually revealed.

In his introduction to the region 2 DVD released by the BFI, Zhangke himself defines the inspiration of the film as follows: [he writes] "once I walked into someone's room by accident and saw dust-covered articles on the desk. Suddenly it seemed as if the secrets of still life fell upon me. The old furniture, the stationary on the desk, the bottles on the window sills and the decorations on the walls all took on an air of poetic sorrow. Still life presents a reality that has been overlooked by many of us. Although time has left deep marks on it, it still remains and holds the secrets of life" This sense of both the past and the present being defined by the seemingly insignificant objects that map the progression of our lives, leaving clues to the mad jumble of emotions and experiences that litter our journey, is further expressed by the chapter-headings, which not only illustrate how the complexities of life can be defined by the possession of something entirely inanimate, but how these apparently innocuous objects serve a greater need in "greasing the wheels" of progress, both politically and sociologically. These objects, "Cigarettes", "Liquor", "Tea" and "Toffee", come to define our social interactions, allowing for the creation of an open forum for discourse or the building of relationships between groups of individuals banding together against this environment of conflict and devastation.

The mark of time, like the watermark that will be left on the mountains and hills as construction of the dam forces the river to rise and the town to become lost to the cause of progress, is another important theme of the film; expressed, not just through the emphasis placed on the characters' search for their absent partners and the mark that they've left on the lives of one another (emotionally speaking), but through the two brief scenes in which we see the discussions between the local residents and those who make the decisions. These scenes illustrate the greater mark that the dam will leave in forcing these people to uproot themselves, to migrate, to follow the water downstream, down river, to a new place to begin a new life with those same memories intact.

Here, the presentation of this world is far from conventional, with Zhangke offering the depiction of a natural landscape with all the surreal and dreamlike abstraction of a post-nuclear holocaust. It is this quality of the film that stands out above all else: the power of the experience; of characters stumbling into situations, witnessing something, translating it and immediately recognising what it is that is being communicated or conveyed. It is a great film, in the sense that it creates characters and scenes that resonate on both an emotional and intellectual level, with great performances, haunting music and stunning cinematography. However, it is an even greater film for what it communicates as a work of ideas; for the particular way in which the film captures this time and place so vividly, becoming a work of real historical significance.

This aspect of the film, and the power that it can have for an audience with the right frame of mind, is best defined by Zhangke himself, who writes; "I entered this condemned city with my camera and I witnessed demolitions and explosions. In the roaring noise and fluttering dust, I gradually felt that life really could blossom in brilliant colours, even in a place with such desperation."

Monday, 22 December 2008

Tuesday, 2 December 2008

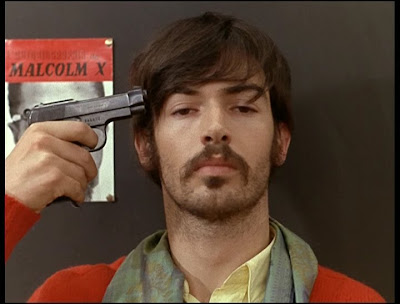

La chinoise

It begins with an image of two hands meeting in the middle of an empty frame, creating an embrace. An embrace, as in the simple act of embracing another; be it another human being, as is the recognisable representation on screen, or more fittingly perhaps, another way of thinking. In this sense, the gesture becomes, at its most basic, a show of solidarity between two individuals, offering the viewer the perfect visual illustration of the collective spirit. A unification of a kind of shared ideology or ideal that offers an immediate contrast to what will eventually become a narrative preoccupied with disparities, ruptures and disagreements; as characters attempting to bring about a collective goal find themselves at odds with the generally accepted way of thinking.

As a creative statement, La chinoise (1967) can be seen as a direct response from Godard to the growing political consensus of the time; predating the eventual chaos of the Paris riots of May 1968 by almost a full year, but also successfully addressing the fact that a change is necessary, if not essential.

Although the film could be categorised (in the most generic sense of the term) a political film, La chinoise is really, at its core, a character study. In essence; a brisk social satire on the relationship between a group of young, bourgeois-minded revolutionaries, playing terrorists from the comfort a suburban apartment building owned by one of the group's parents. Throughout the film, Godard uses this basic narrative framework to explore the relevant ideas of the time, creating a film that could be seen as a sort of infernal parody of Dostoevsky's The Possessed (1872), in the sense that it creates a certain hermetic environment where the five central characters can ruminate on everything from nihilism, to conservatism, to utopias and utilitarianism - always maintaining that the discussions are only interesting because they reveal something more substantial about the characters, their motivations or the relationships within the group, etc - which continually cross back and forth, traversing the political line and into the personal.

In adapting something that at times seems closer to a theatrical presentation, in which a small group of characters address the various topics of discussion - either as a group, or directly to the audience - Godard is able to make the notion of the political commentary far more explicitly than if it were woven into a more conventional narrative framework. Instead, like the directly preceding Two or Three Things I Know About Her (2 ou 3 choses que je sais d'elle, 1967) or Masculin féminin (1966), Godard uses the basic form of the picture to blur the line between a documentary film and a work of fiction. Here, the varying layers of opinion - from characters that are real or adapted from reality, or from characters that are entirely made up - is carefully integrated in an attempt to present both sides of a potential argument.

This notion, of fictional characters interacting with real life, expressing their opinions on actual current events while at the same time acknowledging their own artificiality as creations in a work of fiction, is something that Godard would continue to refine throughout his career; eventually reaching a point with films like For Ever Mozart (1997) and Notre musique (Our Music, 2004), where the the line between layers becomes completely obscured.

Like the first film of Godard's '67 trio, the domestic satire Two or Three Things I Know About Her, La chinoise is effectively structured around a series of dialogues and sketches that establish the political climate of the period, the nature of these characters and their various relationships with one another, and finally their all encompassing views and opinions on concepts such as Maoism, the war in Vietnam and their particular position as Marxist-Leninists. In the past, many critics and audiences have misinterpreted the film as being Godard's ode to Maoism; working almost exclusively as a piece of socio-political propaganda in a similar way to how the influence of Marx is sometimes wrongly interpreted on the thematic foundation of the subsequent Week End (1967). However, it seems unlikely that Godard was being entirely celebratory with his depiction of a self-appointed student commune tackling the issues of the day in a series of ridiculous role-playing games, forthright discussions and the eventual urge for violence and revolution, but rather, using this absurd and provocative notion as a springboard to a series of more interesting discussions and routines.

As a result, attempting to explain the deeper subtext of La chinoise in any kind of greater detail can be a daunting task. After all, who is to say what Godard was really attempting to communicate with the film beyond what is immediately stated? As ever, we can only approach it on a personal level, by making assumptions and describing the experience first-hand. Though the ultimate intent of Godard, the political background of the film and the satirical nature of the presentation can all be seen as off-putting to those disconnected, either geographically or generationally from the events of this period, the basic foundations of the film and the dynamics between the four or five central characters is immediately recognisable. Though it is argued that Godard had a great belief in the ideologies of Mao and the teachings of his "little red book", he nonetheless argues against the beliefs of these central characters, either through the use of other, more informed supporting figures who voice their legitimate, real-life opinion from the fictional framework of the film, or through the actual structure of the picture; reminding the audience that these characters, although well-read and university educated, are still children, and thus, express themselves through childish games and fancy dress.

As withWeek End, the ultimate depiction of the characters here is often so contemptuous that we can only see it as underlining Godard's satirical intentions; as these opinionated young people bleat and pontificate amidst the director's onslaught of ironic visual motifs that seem to conspire to make a mockery out of their objectives and ideals. However, while Godard questions the intentions of his characters, celebrating their vigour and enthusiasm while simultaneously chastising their commitment and approach, the actual characterisation of the performers ensure that the presentation never turns in to caricature or farce.

Throughout the film, these characters - although stylised and often speaking dialog that works as a kind of call and response argument - are completely believable, and it is to the often overlooked credit of Godard as a director of actors that these individuals register as just that; each a single character, clashing against an idea or ideal that is represented by the other, attempting to govern a collective utopia, but each being too selfish or too impatient for such dreams to ever be fulfilled. Here, the film benefits greatly from the lead performance of the young actor Jean-Pierre Léaud as the drama student Guillaume, whose playful pretension and look-at-me sense of theatricality make him an obvious and charismatic leader for the group, which also includes Anne Wiazemsky as would-be philosopher Veronique, Juliet Berto as a character reminiscent of a younger incarnation of Marina Vlady's character in "2 or 3 Things" (due largely to her farm-girl roots and casual prostitution) and Michel Séméniako as the conflicted and ultimately far more thoughtful of the group, Henri.

The way that these characters clash and contrast, brought down by their own personal relationships in the usual Godardian form of "couples" (e.g. both the relationship between men and women, and the more obvious coupling of sound as applied to image) further illustrates that this is a character study, and not simply a "political film". Even during the key scene, in which Veronique discusses the current cultural situation with the real-life philosopher and radical thinker Francis Jeanson - who criticises the actions of the group as childish and uninformed in a way that adds weight to the film's counter argument and to Godard's own potential perspective on his characters - the discussion is still important on the personal level, in what it reveals about Veronique as an individual. That this discussion takes place on a train, itself always moving in one direction, progressing, is incredibly apt; Veronique and Jeanson may be heading in the same direction, but they will never arrive at the same destination, not unless they can work together to form the correct course of action in place of this opposing adolescent folly.

From the very beginning, Godard defines La chinoise as a work in progress; something that is in the process of being made, always in motion, organic and alive with ideas. The familiar self-reflexive, deconstructive notion of fictional characters being treated to their own documentary feature, again, like Masculin féminin or Two or Three Things I Know About Her. The appearance of clapper boards, microphones and even the film camera itself skew the recognisable position between fiction and documentary; how can we be watching the film if the film itself is still being made?

It conveys that aspect of confusion apparent in the punning title, rife with double meanings. On the most obvious level, it is a reference to the Chinese Cultural Revolution of 1966, introducing the theme of politically-minded young people ready to heed the advice of Chairman Mao in the pursuit of the Communist ideal. However, in French, "Chinoise" can also refer to a kind of nonsense; "chinoiserie" = "an unnecessary complication" or "c'est du chinois" = "it's all Greek to me"; a lead-off from the scene in Made in U.S.A.(1966) in which Anna Karina slants her eyes, looks into the camera and confesses a state of confusion.

La chinoise is generally characteristic of Godard's shift into more radical forms of filmmaking beginning around the time of Pierrot le fou (1965) but really becoming more focused throughout 1966 and 1967; the pivotal period, pre-fin de cinema, during which the filmmaker released three completely different though no less radical features back to back. Even so, the familiar Godardian-look is still present; the use of inter-titles to offer commentary on the image and sometimes beyond it, here stencilled onto the walls of the apartment as well as intercut in the style of silent cinema; the incredible use of bold primary colours, like Le mépris (Contempt, 1963) or Une femme est une femme (A Woman is A Woman, 1961); the use of music, song and dance, of characters playing a role, poor Napoleon in his Theatre Year Zero; the extraordinary use of sound and shot composition. The pop-cultural references alongside literary quotations, highbrow and lowbrow, Marvel Comic superheroes and hand-coloured news clippings; ironic pop songs, masks and toys; in every scene the film is a perfect example of how to create an interesting frame on a limited budget as well as underlining the personalities of these characters, their approach to the situations and the greater political context that lurks on the edges of the drama.

Though mostly a playful film in tone, La chinoise hints at an escalating air of violence and political unrest, both in the cultural sense and in the sense of Godard's career as a whole; a violence that would eventually explode in the final moments of the apocalyptic Week End; in which car-crashes and the deliberate annihilation of literary creations places society on a road to inevitable destruction, and where the differences between cannibalism and consumerism are not that far removed. From here, films like One Plus One (1968) andLe Gai savoir (The Joy of Learning, 1968) would continue the formal experimentation, but would also make the political aspect more direct and the characterisation deliberately unclear. Conversely, a film like La chinoise seems perfectly structured around these individuals, so that the political commentary feels genuine, essentially because its coming from the characters and creating the drama, as opposed getting in the way of it.

As a creative statement, La chinoise (1967) can be seen as a direct response from Godard to the growing political consensus of the time; predating the eventual chaos of the Paris riots of May 1968 by almost a full year, but also successfully addressing the fact that a change is necessary, if not essential.

Although the film could be categorised (in the most generic sense of the term) a political film, La chinoise is really, at its core, a character study. In essence; a brisk social satire on the relationship between a group of young, bourgeois-minded revolutionaries, playing terrorists from the comfort a suburban apartment building owned by one of the group's parents. Throughout the film, Godard uses this basic narrative framework to explore the relevant ideas of the time, creating a film that could be seen as a sort of infernal parody of Dostoevsky's The Possessed (1872), in the sense that it creates a certain hermetic environment where the five central characters can ruminate on everything from nihilism, to conservatism, to utopias and utilitarianism - always maintaining that the discussions are only interesting because they reveal something more substantial about the characters, their motivations or the relationships within the group, etc - which continually cross back and forth, traversing the political line and into the personal.

In adapting something that at times seems closer to a theatrical presentation, in which a small group of characters address the various topics of discussion - either as a group, or directly to the audience - Godard is able to make the notion of the political commentary far more explicitly than if it were woven into a more conventional narrative framework. Instead, like the directly preceding Two or Three Things I Know About Her (2 ou 3 choses que je sais d'elle, 1967) or Masculin féminin (1966), Godard uses the basic form of the picture to blur the line between a documentary film and a work of fiction. Here, the varying layers of opinion - from characters that are real or adapted from reality, or from characters that are entirely made up - is carefully integrated in an attempt to present both sides of a potential argument.

This notion, of fictional characters interacting with real life, expressing their opinions on actual current events while at the same time acknowledging their own artificiality as creations in a work of fiction, is something that Godard would continue to refine throughout his career; eventually reaching a point with films like For Ever Mozart (1997) and Notre musique (Our Music, 2004), where the the line between layers becomes completely obscured.

Like the first film of Godard's '67 trio, the domestic satire Two or Three Things I Know About Her, La chinoise is effectively structured around a series of dialogues and sketches that establish the political climate of the period, the nature of these characters and their various relationships with one another, and finally their all encompassing views and opinions on concepts such as Maoism, the war in Vietnam and their particular position as Marxist-Leninists. In the past, many critics and audiences have misinterpreted the film as being Godard's ode to Maoism; working almost exclusively as a piece of socio-political propaganda in a similar way to how the influence of Marx is sometimes wrongly interpreted on the thematic foundation of the subsequent Week End (1967). However, it seems unlikely that Godard was being entirely celebratory with his depiction of a self-appointed student commune tackling the issues of the day in a series of ridiculous role-playing games, forthright discussions and the eventual urge for violence and revolution, but rather, using this absurd and provocative notion as a springboard to a series of more interesting discussions and routines.

As a result, attempting to explain the deeper subtext of La chinoise in any kind of greater detail can be a daunting task. After all, who is to say what Godard was really attempting to communicate with the film beyond what is immediately stated? As ever, we can only approach it on a personal level, by making assumptions and describing the experience first-hand. Though the ultimate intent of Godard, the political background of the film and the satirical nature of the presentation can all be seen as off-putting to those disconnected, either geographically or generationally from the events of this period, the basic foundations of the film and the dynamics between the four or five central characters is immediately recognisable. Though it is argued that Godard had a great belief in the ideologies of Mao and the teachings of his "little red book", he nonetheless argues against the beliefs of these central characters, either through the use of other, more informed supporting figures who voice their legitimate, real-life opinion from the fictional framework of the film, or through the actual structure of the picture; reminding the audience that these characters, although well-read and university educated, are still children, and thus, express themselves through childish games and fancy dress.

As withWeek End, the ultimate depiction of the characters here is often so contemptuous that we can only see it as underlining Godard's satirical intentions; as these opinionated young people bleat and pontificate amidst the director's onslaught of ironic visual motifs that seem to conspire to make a mockery out of their objectives and ideals. However, while Godard questions the intentions of his characters, celebrating their vigour and enthusiasm while simultaneously chastising their commitment and approach, the actual characterisation of the performers ensure that the presentation never turns in to caricature or farce.

Throughout the film, these characters - although stylised and often speaking dialog that works as a kind of call and response argument - are completely believable, and it is to the often overlooked credit of Godard as a director of actors that these individuals register as just that; each a single character, clashing against an idea or ideal that is represented by the other, attempting to govern a collective utopia, but each being too selfish or too impatient for such dreams to ever be fulfilled. Here, the film benefits greatly from the lead performance of the young actor Jean-Pierre Léaud as the drama student Guillaume, whose playful pretension and look-at-me sense of theatricality make him an obvious and charismatic leader for the group, which also includes Anne Wiazemsky as would-be philosopher Veronique, Juliet Berto as a character reminiscent of a younger incarnation of Marina Vlady's character in "2 or 3 Things" (due largely to her farm-girl roots and casual prostitution) and Michel Séméniako as the conflicted and ultimately far more thoughtful of the group, Henri.

The way that these characters clash and contrast, brought down by their own personal relationships in the usual Godardian form of "couples" (e.g. both the relationship between men and women, and the more obvious coupling of sound as applied to image) further illustrates that this is a character study, and not simply a "political film". Even during the key scene, in which Veronique discusses the current cultural situation with the real-life philosopher and radical thinker Francis Jeanson - who criticises the actions of the group as childish and uninformed in a way that adds weight to the film's counter argument and to Godard's own potential perspective on his characters - the discussion is still important on the personal level, in what it reveals about Veronique as an individual. That this discussion takes place on a train, itself always moving in one direction, progressing, is incredibly apt; Veronique and Jeanson may be heading in the same direction, but they will never arrive at the same destination, not unless they can work together to form the correct course of action in place of this opposing adolescent folly.

From the very beginning, Godard defines La chinoise as a work in progress; something that is in the process of being made, always in motion, organic and alive with ideas. The familiar self-reflexive, deconstructive notion of fictional characters being treated to their own documentary feature, again, like Masculin féminin or Two or Three Things I Know About Her. The appearance of clapper boards, microphones and even the film camera itself skew the recognisable position between fiction and documentary; how can we be watching the film if the film itself is still being made?

It conveys that aspect of confusion apparent in the punning title, rife with double meanings. On the most obvious level, it is a reference to the Chinese Cultural Revolution of 1966, introducing the theme of politically-minded young people ready to heed the advice of Chairman Mao in the pursuit of the Communist ideal. However, in French, "Chinoise" can also refer to a kind of nonsense; "chinoiserie" = "an unnecessary complication" or "c'est du chinois" = "it's all Greek to me"; a lead-off from the scene in Made in U.S.A.(1966) in which Anna Karina slants her eyes, looks into the camera and confesses a state of confusion.

La chinoise is generally characteristic of Godard's shift into more radical forms of filmmaking beginning around the time of Pierrot le fou (1965) but really becoming more focused throughout 1966 and 1967; the pivotal period, pre-fin de cinema, during which the filmmaker released three completely different though no less radical features back to back. Even so, the familiar Godardian-look is still present; the use of inter-titles to offer commentary on the image and sometimes beyond it, here stencilled onto the walls of the apartment as well as intercut in the style of silent cinema; the incredible use of bold primary colours, like Le mépris (Contempt, 1963) or Une femme est une femme (A Woman is A Woman, 1961); the use of music, song and dance, of characters playing a role, poor Napoleon in his Theatre Year Zero; the extraordinary use of sound and shot composition. The pop-cultural references alongside literary quotations, highbrow and lowbrow, Marvel Comic superheroes and hand-coloured news clippings; ironic pop songs, masks and toys; in every scene the film is a perfect example of how to create an interesting frame on a limited budget as well as underlining the personalities of these characters, their approach to the situations and the greater political context that lurks on the edges of the drama.

Though mostly a playful film in tone, La chinoise hints at an escalating air of violence and political unrest, both in the cultural sense and in the sense of Godard's career as a whole; a violence that would eventually explode in the final moments of the apocalyptic Week End; in which car-crashes and the deliberate annihilation of literary creations places society on a road to inevitable destruction, and where the differences between cannibalism and consumerism are not that far removed. From here, films like One Plus One (1968) andLe Gai savoir (The Joy of Learning, 1968) would continue the formal experimentation, but would also make the political aspect more direct and the characterisation deliberately unclear. Conversely, a film like La chinoise seems perfectly structured around these individuals, so that the political commentary feels genuine, essentially because its coming from the characters and creating the drama, as opposed getting in the way of it.

Tuesday, 18 November 2008

The Third Part of The Night

Like Guernica, Picasso's extraordinary painting, Andrzej Żuławski's The Third Part of The Night (Trzecia część nocy, 1971) expresses, in a very immediate but also rather thought-provoking way, the concept of genocide. Here, the idea is developed through an incredibly frightening evocation of the period of German occupation in Poland during the Second World War, in which the general background of conflict and persecution is used, as in Guernica, not simply to establish a particular historical context, or to grant the audience a greater sense of perspective, but as a symbolic expression of the central character's own tortured descent into the depths of memory, identity, mortality and despair.

In this sense, the thematic design of the film is in some ways reminiscent of Russian filmmaker Elem Klimov's similar World War II allegory, Come and See (Idi i smotri, 1985), in which the more broadly recognisable conventions of wartime iconography - the conflict and the struggle - are used to express the disintegrating emotional perspective of its young central character within that almost apocalyptic vision of destruction and devastation that the Second World War would come to represent, both historically and creatively.

However, if Come and See was as much about the madness of war in the literal, ideological sense, then Żuławski's film goes beyond even that; offering what one character in the film refers to as a "complicated vortex", in which the madness of war can be seen as an extension of the devastating events that transpire during the film's shattering opening sequence. Here, grief and guilt circle around these characters, leading them to explore what the late British filmmaker Derek Jarman once referred to as 'an investigation of the past by way of the present', while simultaneously placing them within the recognisable dramatic context of what another character knowingly describes as "a medieval darkness."

As this dialogue might indicate, the film offers a strange and often hallucinatory narrative effectively about a character spiralling out of control; with the actual look and the texture of the film conveying this feeling of freefall by switching, almost at random, from elements of over-the-top surrealism to something almost resembling a conventional genre film. However, these half-formed, never fully developed tonal shifts serve a purpose in contextualising the uncertainly of the life and death theme that can be taken as the most obvious reading of the film's literally apocalyptic climax. As the events of the opening scenes create, not only a circular effect that ties both ends of the narrative together, but a kind of ripple effect that is followed all the way through the narrative, leading to the curious chronological structure, the exaggerated performances and the jarring shifts from violence to almost religious transcendence.

In keeping with this, the dialogue seems littered with clues that continually push us towards a more psychological or even allegorical reading of the text. For example, the early scenes between Marta (Małgorzata Braunek) and Michal (Leszek Teleszyński) - both doubles for other characters, both doppelgangers attempting to find the familiar in different beings - where the dialog is seemingly designed to express the issues of memory and identity that hang over the story, as these two characters attempt to identify one another; "one is a reflection" says Marta, "and you yourself are the mirror."

As Marta dresses Michal's wounds after their initial meeting, he opines "I've been finding you again". "Yes", she replies, "in other people who aren't us". The dialog is continually changing our interpretation of what we are experiencing; are we witnessing the last few seconds of life from a young man cut down in the film's opening massacre, or a psychological metamorphosis, supposedly illustrating how war can change a man, both mentally and physiologically? As the character Marta herself explains, somewhat self-reflexively, "such things often happens in the midst of war - amongst the lice and the blood and the muck", as the characters are forced to become detached from their surroundings and their situation, looking in on themselves as if observing the lives of others, while simultaneously "sinking into a world where all things have become alike". It is the expression of war, not just as the machine that turns the cogs that eventually lays waste to the human spirit, but as a veritable hall of mirrors, revealing and then distorting a series of revelations that not only leave the audience perplexed, but the characters as well.

As a result, it is a film that exists on the fringes of reality, blurring the lines between dream and certainty, memory and fiction; as holocaust imagery is placed alongside the use of deliberate religious symbolism to create an even more horrific atmosphere of dread and despair. Meanwhile, the development of a complex and emotionally fragile chronology of events, punctuated throughout by moments of intense violence and surreal abstraction, finds our character plunged headlong into a central mystery that blends elements of actual historical fact with more abstract ideas that seem to push the film further into the bizarre and often existentialist realms of writers like Kafka, Sartre or Borges.

All of this is apparent from the film's memorable opening sequences; in which a reading from the Book of Revelations is juxtaposed against a disquieting montage of early morning landscapes and stark, unforgettable violence. The series of shots that introduce the film also work towards establishing something of a tone, both visually and atmospherically, that will intensify throughout; with the dark, menacing shots of the Polish countryside - a veritable black mosaic of backlit tree branches reflected on murky, autumnal lakes that foreground a no doubt once opulent country manner house, where the characters have taken refuge from the continuing conflict and persecution - giving us the central location where the story will both begin and end with that scene of devastation played out from two very different perspectives.

The quality of the images presented in this sequence are contrasted perfectly by the reading of the text; as the themes of dread and destruction and the tone of the voice suggest a sense of fear and uncertainty. From here, Żuławski confronts us with the film's first and most penetrating depiction of violence; as the interior of the house is suddenly invaded by soldiers on horseback, who strike Helena (again played by Małgorzata Braunek) with the butt of their rifles, as Michal and his young son watch with horror from the neighbouring trees. Though again, captured in a very matter of fact approach, with the camera work of Witold Sobociński making great use of the handheld, pre-Steadicam style to exaggerate the drama and confusion, the scene has an undercurrent of abstract dream-logic. The simple image of a horse and guard charging into this quiet country manor house, combined with the look of sheer horror on the face of Helena, seems to exist somewhere between the fantastical realms of a Terry Gilliam film (The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, 1988 perhaps) and the devastating horror of a Pier Paolo Pasolini (cf. Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, 1975).

According to an interview that accompanies the recent region 0 DVD, the initial genesis of The Third Part of The Night came from Żuławski's conversations with his father Mirosław about his own experiences during the Nazi occupation of Lwow, and in particular, his time with The Rudolf Weigl Institute, where Mirosław was one of the many Polish intellectuals - alongside figures like the mathematician Stefan Banach and the musician and conductor Stanislaw Skorwaczewski - who found protection in the institution as carriers for an experimental Typhus vaccine. Like Mirosław, the character of Michal uses the institute to hide out from the threat of oppression, as those closest to him are murdered, hounded or rounded up into the backs of trucks and trailers, never to be seen again.

Here he enters into what film critic Michael Brooke describes as an "inverted value system that assigns the highest social status to human guinea-pigs offering themselves as a food supply for laboratory bred lice". It is in these sequences that Żuławski's documentarian approach to detail is the most jarringly apparent. And yet, even as the camera lingers on the smallest of authentic details, the sheer absurdity and nightmarish undercurrent of this situation can't help creating a more surreal and ultimately distressing Kafkaesque nightmare; as Michal and his comrades become (essentially) no better than corpses - food for the insects - living an almost purgatory like existence as ghosts, neither alive nor dead.

This central concept of the void between life and death and the further blurring of perceptions and, more importantly, identities, is a key theme of The Third Part of The Night; with the vague shifting between time and memory - as if moving through the various layers of a dream - propelling the narrative towards its confounding and enigmatic final. Here, our protagonist must stare into the hollowed face of death to find only the bleak abyss staring back at him; illustrating that Żuławski wasn't simply prefiguring the ideas articulated in Klimov's great work, but those that would later be expressed in director David Lynch's trilogy of psychological metamorphosis - as represented by the films Lost Highway (1997), Mulholland Dr. (2001) and Inland Empire (2006).

Like those films, The Third Part of The Night presents layers of both reality and reflection, in which a frenzied mystery is shaped by the contrast between the two strands of what we see and what we believe. A film where a character on the very edge of sanity, puts back the pieces of a tragic event that changed the course of his young life, and instead of finding a clear image, is presented with a fragmented patchwork of terror and uncertainty.

In this respect, it is a film is a work of layered interpretations; where images of doorways and staircases that represents the movement from one shifting reality to another, takes dominance over the mise-en-scene. The sense, of moving between words, memories and realities abstracts the drama even further, creating a bleak kaleidoscope of images and ideas similar in execution to the climax of Takashi Miike's masterpiece Audition (Ôdishon, 1999). As the film progresses, the tenuous hold that Michal has on reality becomes strained, and he is drawn, almost supernaturally, through layers of reflection. As the atmosphere of the third act becomes much more intense, the character is led into a literally hellish underworld; a Dante's Inferno, where a series of grisly discoveries in a literal hospital of horrors - filled with what author Daniel Bird refers to as "a Grosz-like gallery of the grotesque" and a series of "Francis Bacon-like bodies covered in lice cages in an otherwise darkened cell" - conspire to push the character further into the bowels of the institution, where the secrets of his fate will be revealed.

However, the answer to the film's most pertinent question evades both the character and the audience, obscured as it is by conflicting narrative perspectives; reducing the plight of this character to the level of a Rorschach construct, in which the answer to the most significant question of all can be found only as a reflection on the face of death itself. As a result, it will be a difficult film for many viewers, not simply in regards to the atmosphere and the imagery that is created, but in the film's often confusing disregard for logic and convention; where the whole film, for the most part, seems beyond the realms of easy categorisation, or even critique.

More than anything, it reflects the notion of a cinema of dreams (or nightmares); with the often ugly, ecstatic nature of Żuławski's direction and the heightened, almost exaggerated performances of his cast creating a tone that lingers long in the imagination. Where the characters ripple and convulse in irregular, epileptic spasms, while those unforgiving, wide-angle lenses are continually pushed right into the faces of the actors in order to capture every uncomfortable moment of pain and despair.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Schalcken the Painter (1979)

Schalcken the Painter [Schalcken the Painter [Leslie Megahey, 1979]: This is a film I first saw around four years ago. At the time I found...

-

Schalcken the Painter [Schalcken the Painter [Leslie Megahey, 1979]: This is a film I first saw around four years ago. At the time I found...

-

In discussing the brief snippet from the ever contentious Uwe Boll's no-doubt harrowing new film Auschwitz (2011) - particularly the way...

-

The Image of Happiness or: 'the black leader' "The first image he told me about was of three children on a road in Icel...