The title, Bleak Moments (1971), is as accurate a two-word description of the general feeling and tone of the finished film that one could ever hope to find; expressing, at its most basic, the feelings of hopelessness and desperation that accumulate throughout the course of the film as these characters simply pass the time in their cramped, domestic living-spaces, looking out at a world in the hope of finding the warmth and colour of everyday life, only to find instead the sad rejection and emptiness of their own situations reflected back at them. It is the endless spiral of social anxiety presented at its most unforgiving, as each attempt to break out of this kind of self-imposed purgatory and confront the boundaries of life head-on leads only to more embarrassment and failure; where the only respite is those brief moments when the characters find the time to take their minds off the gruelling responsibilities or anticipations of life and just think.

Described on its initial release by Roger Ebert as a "new kind of movie", one that "considers, with almost frightening perceptiveness, the ways people really behave towards each other", Bleak Moments would mark the arrival of the now-highly acclaimed director Mike Leigh, who developed the film - his first film for cinema - from his earlier stage-production of the same name. Although one could argue that as a complete picture this debut film lacks much of Leigh's later creative subtly and that sense of the sweetness of life to undercut the more uncomfortable feelings of quiet desperation so central to the lives of his characters and the various situations that they have been placed in, we can at least recognise the typical Leigh aesthetic in the mining of everyday life to create the parameters of engaging drama, or perhaps in the entirely convincing performances of his actors, who embody these roles, largely because they were able to develop them alongside the director, living these lives and drawing on their own experiences to make the actions of the characters and the pain that they feel all the more believable.

In keeping with the greater emphasis on character interaction the plot is incredibly straightforward. Essentially a brief snapshot into the life of Sylvia (Anne Raitt), a lonely secretary who shares her suburban home with a disabled sister, Hilda (Sarah Stephenson), who she is expected to offer round the clock supervision to, often at the expense of her own happiness or social satisfaction. Her downtime, if any, is spent entertaining her ditzy friend and co-worker Pat (Joolia Cappleman) or, if possible, attempting to forge a relationship with the shy grammar school teacher Peter (Eric Allen), who drifts in and out of her life. There is also the character of the lodger, Norman (Mike Bradwell), a shy young man, head-down, hair covering his face and further muffling his already softly-spoken northern accent, who lives in a makeshift bedsit in the character's garage where he alternates between printing fliers for his bosses at work or strumming out yearning folk songs on his battered old guitar.

These characters meet regularly but rarely speak, choosing instead to linger on the fringes of the frame, making pained attempts at conversation that go nowhere. To accentuate the discomfort of these scenes, the shots are allowed to play out for what seems like an eternity; establishing a particular rhythm that perfectly underlines that feeling of the awkward - why didn't I say it - sense of inarticulate longing. Expressing perfectly that failure to express through the recognisable pattern of failed conversation - the think, open mouth, a sigh, a false start, conversation stalling, think again, a look, a nod of approval, an uttered word, hushed and mumbled, a pause, a false start, a look of confusion - repeating itself until the words begin to take shape. In this vision of loneliness and repressed desperation the whole film becomes suffocating to watch; with that think and heavy, pregnant with the anticipation of something mood never alleviating throughout its stifling 111 minute running time, as the accretion of these bleak moments creates a depressing and overwhelming effect.

Ebert defined this quality as such: "Bleak Momentsis not entertaining in any conventional way. This is not to say for a moment that it is boring or difficult to watch; on the contrary, it is impossible not to watch. [But] This movie deals so basically with the pain and utter frustration of life that we may, after all, find it too much to take." It is in this almost searing social-anguish, as this collection of characters attempt to co-exist in the everyday world, though ill-equipped to deal with the various pitfalls as a result of their own self-conscious quirks and idiosyncrasies, that the characteristics of the film is defined. Not simply in terms of the general structure of scenes or the goals and ambitions of these characters, but in the actual putrid air that Leigh is able to create through his presentation of rooms haunted by characters unable or unwilling to interact with life; all the while being crippled and torn apart by their repressed feelings of guilt, love, longing and loss, all brought painfully into focus in the numerous extended sequences of uncomfortable silence and embarrassing personal confession.

In this respect, the film is as much a social chronicle of a certain kind of lifestyle as it is a dramatisation, presented in a densely atmospheric, heavily stylised and deeply austere cinematic manner, in which every tool at Leigh's disposal is used to prolong the quiet suffering of these characters and their endless days of drift and nothing. Although there is a sense of humour to certain aspects - the particular absurdity of situations and the natural comedy of life as characters crack jokes or cringe at their own suffering faux pas' - the film remains much more serious in tone than many of Leigh's more widely seen films: with the general feeling being closer to something like Meantime (1984) or Naked (1993), though even that was marked by Johnny's (David Thewlis) constant quips and puns. Like those films, the drama of Bleak Moments is captured within an exhausting, highly minimalist mise en scene that recalls the Fassbinder of Why Does Herr. R Run Amok? (Warum läuft Herr R. Amok?, 1970), the Bergman of Cries and Whispers (Viskningar och rop, 1972) and the Pialat of La Gueule ouverte (The Slack-Jawed Mug, 1974); where the location and production design and the closeness between characters unable to feel intimacy is explored.

From this, there's no escape for Sylvia, who tires valiantly to connect with the shy Peter and the lodging Norman, but finds both men too damaged or too introvert to really get to grips with. The drama reaches an apex with two of the most painful scenes of Leigh's cinema to date. In the first scene, Sylvia and Peter go for a meal at an over-lit, largely vacant Chinese restaurant. Once there, Peter becomes agitated, berating the snooty waiter over trivial reactions and off-setting the atmosphere with his constant, ill-at-ease scowl. As the evening progresses the couple barely speak; with Sylvia instead left to ponder and observe the solitary serenity of the restaurants only other customer, who sits huddled in the corner, happy in the company of himself. This scene acts as the catalyst for the second scene, in which the couple go back to Sylvia's house for coffee and chat. During the scene, the sense of desperation welling up within Sylvia comes close to breaking point, as she confesses her desires for Peter and extends an invitation to bed. Peter, affronted and somewhat disgusted at such baseless, brazen provocation, leaves; making a painful, humiliating and emotionally raw sequence all the more heartbreaking.

Throughout the film these characters attempt as best they can to improved their social situation, but instead, end up repeating the same mistakes ad infinitum. In achieving the requisite emotional pull from this cold and loveless film, Leigh's genius, apparent even at this early stage of his career, is to allow his actors the room to move between the different emotional shades, letting the characters drift from moments of cold resentment to painful longing, often within the confines of a single scene. To emphasise this feeling, the direction of the film, in the technical sense, seems intent on stripping away all (if any) of the extraneous baggage that might reduce these situations to the level of mere melodrama; with Leigh muting the colours of the costumes and production design to the level or near monochrome, so that these characters are quite literally existing, or attempting to exist, in this grey and depressing milieu.

This particular aspect is brilliantly defined by Fernando F. Croce who evocatively describes "figures shambling down overcast London streets with leafless trees, or pinned against greenish domestic interiors." Leigh exaggerates this by reducing the score to the brief acoustic interludes of Norman, as he spends his nights cocooned in Sylvia's garage, plucking and strumming his guitar as the world continues to turn. In these scenes one may feel oddly compelled to describe the mood as 'intimate', and yet it becomes clear very early into the film that these characters are incapable of experiencing such frank, emotional honesty. The only characters that seem free from these rigid and soul destroying social restraints are Sylvia's sister Hilda, whose mental disorder offers a certain ignorance to the pressures of everyday life, and the mother of Sylvia's workmate Pat, who is forced to spend her life cooped up in bed, oblivious to the social climate of the time.

Sunday, 10 May 2009

Saturday, 2 May 2009

Visitor Q

Beginning with a vague preamble on the use of digital video in achieving that contrast between the abstract and the real...

One of the most interesting developments to occur in contemporary cinema over the course of the last ten years has been the increase in availability of digital filmmaking technology and the obvious benefit that this has offered to filmmakers, not least in terms of reducing budgets and production schedules, but in looking at the world from a new perspective. From Lars von Trier's The Idiots (Idioterne, 1998) to David Lynch's Inland Empire (2006), the look and more importantly the feel of digital photography has further obscured the recognisable line between drama (i.e. artifice: the filming of a performance within a carefully constructed frame) and reality. The "look", as it were, is closer to a perceived realism as presented by that of reality television, docudrama or a fly on the wall; the sense that we are seeing something closer to reality because the sparseness of its images, the relaxed nature of its performances and the awkward passages usually removed or tightened by the editing process remind us of the unrehearsed spontaneity of everyday life.

The feel of digital cinema (discounting the more pioneering digital work of films like Attack of the Clones (2002) or Zodiac (2007), in which the attempt is to make digital look as glossy and well-defined as 35mm celluloid) is the stuff of wedding videos or the filmed performances of a high school musical. The effect is more recognisable to our own (non-professional?) experiments with filmmaking in the domestic sense; something that worked in favour of a film like Thomas Vinterberg's masterful Dogme95 experiment Festen (The Celebration, 1997), in which the appearance of a self-shot family portrait plays on the idea of documenting family celebrations in order to preserve that particular memory or occasion. By adopting this specific style, the filmmaker is able to make convincing those scenes that may have previously overwhelmed us, or become an obstruction as a result of their melodramatic superfluities.

Would an audience have believed Christian's (Ulrich Thomsen) fraught dinnertime speech delivered to his father (Henning Moritzen) or the anxious quaver of desperation as he revealed the tragic back-story of his suicidal twin-sister to a room-full of dumbfounded relatives and guests in Vinterberg's aforementioned magnum-opus if it had been shot with all the beauty and grace of a Merchant-Ivory production? Or does the recognisable candid-camera-like intrusion that digital video presents create a more reasonable window into the world in which the exaggerated melodrama of the plot becomes almost plausible?

The use of video implies "realism", but only because of these associations and the natural shock of seeing images stripped of their usual cinematic-gloss. However, it also possesses a more powerful contrast; with the actual look of video, in comparison to 35mm film (or even Super8 or 16mm film) actually becoming more abstract and surreal in both texture and appearance. Although we might identify something apparently truthful (i.e. recognisable) in the presentation of these digital pictures, there is also that alien quality, which exaggerates and distorts.

This particular contrast works perfectly in director Takashi Miike's gloriously subversive satire, Visitor Q (Bijitā Kyū, 2001); a film in which the required use of digital video actually shapes, not only the look and feel of the film, but the actual development of its narrative. The film, best described as a chaotic snapshot of contemporary middle-class Japanese domesticity, is essentially a demented pastiche of the Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini's classic psychological drama, Teorema (1968); a film in which the notion of a seductive young corruptor of innocence - as personified in that particular film by a calculated Terrance Stamp - is here turned upside down; with Miike and his screenwriter Itaru Era turning a stifled, claustrophobic investigation into the unspoken psychosexual desires of a family of Italian intellectuals into a slapstick farce of animated subtleties and stark, almost Buñuelian satirical intentions.

In both films the plot could be described in a single-line; "A stranger is accepted into a normal family and becomes a catalyst for radical change." As the critic Chris Campion notes in his short-essay included with the Tartan Video Region 2 DVD release of the film, "Pasolini's movie can be seen as both a political and religious allegory; the disintegration of the nuclear family symbolising the rejection of bourgeois values."

In Visitor Q, this initial set-up is turned inside out. In the Pasolini film, the change is for the worse, and the tone of the movie is bleak and filled with deception. However, in Miike's film, the change is for the better, and although this is a picture filled with violence and brutality, the tone is ultimately hopeful. You can feel it in the warm swell of Kôji Endô's subtle score as it lifts the scenes at disarming moments throughout; turning the flashes of degradation and dismemberment into acts of tender mercies.

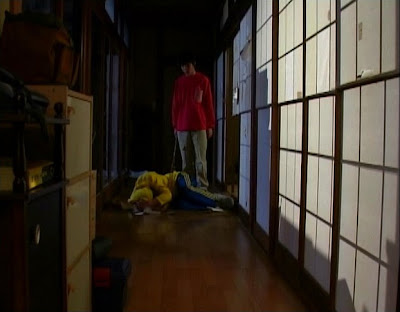

In Miike's film, the wandering stranger, played here by the actor and director Kazushi Watanabe, positions himself at the heart of the Yamazaki household, where the family, consisting of father Kiyoshi (Kenichi Endo), mother Keiko (Shungiku Uchida), daughter Miki (Reiko Matsuo, billed here as 'Fujiko') and son Takuya (Jun Mutô) are on the precipice of absolute chaos. The lingering air of apocalyptic dread, dysfunction, disorder and disarray is established in the very first scene, with the character of Miki boldly asking the question on-camera, but also to-camera (and by extension, questioning the natural voyeurism of the cinema and the home-cinema audience) - "You wanna know the truth about the youth of today... to predict the future of Japan... this hopeless future?" Miike's provocative inter-title, which then audaciously asks "have you ever done it with your dad?" establishes the dominant tone of the film, finding the middle-ground between absurd parody and actual documentary; polemic and pastiche.

Beyond the more immediate display of the film's humour and approach, Visitor Q demonstrates a keen awareness of the various societal concerns and issues currently facing the modern Japan. It touches on all the major issues, including sexual abuse, prostitution, drug-dependency, schoolyard bullying and the gradual erosion of the archetypical family unit, in which father and mother are no longer in a position to fulfil the basic requirements of the patriarch/matriarch model of maintaining an efficient, well-functioning household.

It is not simply a work of empty shock or spectacle (although it can - no doubt - be approached on such a level), but rather a film that should be appreciated and experienced as a serious commentary on the cycle of violence as illustrated by a family in which the roles of the father and mother have become debased and obscured. A world in which the father is a disgraced news reporter exploiting the decline of his family as way to claw back a sense of respect from his associates and peers, and where the mother has become a tortured heroin addict, turning tricks in order to fund a habit that allows an escape from the regular beatings of her wayward teenage son.

The film implicates the failure of the parents in the failure of their children; for instance, the father's emasculation/humiliation at the hands of a gang of teenage hoodlums' gives way to the son's own torment from the ritualistic abuse of his classmates. This in turn is expressed through his own violent attacks on his mother, who now finds solace in the needle, or in the loveless embrace of anonymous sex-starved salary men, and the obvious parallels here with her own daughter, lost in the big city and also selling sex, until the cycle of failure and abuse, as it is passed back and forth between the generations, becomes painfully clear.

We can see similar issues presented in other Japanese films released around the same period as Miike's film, including the director's own off-the-wall musical satire The Happiness of the Katakuris (Katakuri-ke no kōfuku, 2001), in which the notion of the family in the traditional sense is again documented with a perverse and darkly comic approach that obscures the underlining seriousness of its message. Added to this a film like Shinya Tsukamoto's blistering Bullet Ballet (1998), in which the growing divide between the generations and the punishing loneliness of middle-class Japanese existence is projected against a plot that riffs on Taxi Driver (1976) and Neil Jordan's Mona Lisa (1986); as the characters find escape in nihilistic violence and self-punishment to awake them from the numbing slumber of everyday life.

Such concerns are also very much apparent in the J-horror movement of the late 1990s and early 2000s, as films like Ring (1998) and Pulse (Kairo, 2001) depict the growing disconnection between a generation who find comfort in technology; consigned to a world in which even our ghosts are forced to wander the streets in a lonesome, never-ending limbo. The issues facing the youth of Japan, as alluded to by the presentation of the son, Takuya, are also documented in Shunji Iwai's great film, All About Lily Chou-Chou (Rirī Shushu no Subete, 2001); another picture that uses digital video to abstract the presentation of the world but to also create a vague association with reality.

If Miike's use of video abstracts the presentation, then the line between the viewer and the viewed is further obscured by the position of the lead character, who himself is seen documenting the proceedings with his own pocket-video camera; creating an odd sense of confusion as the story literally consumes itself. The footage shot by the character is as much a part of the film as the footage shot by Miike's frequent cinematographer Hideo Yamamoto, with the distinction between the two forms creating a further blurring of perspectives, as we are forced to question if the strange shifts into more abstract or fantastical moments of surreal expression are real or simply symbolic.

As the writer Tom Mes suggests in his book Agitator: The Films of Takashi Miike (FAB Press, 2003), the shifts in the narrative and the construction of these characters are nothing less than allegorical. Although it all seems incredibly haphazard and thrown together with a complete disregard for convention, there is a strange kind of logic at work in which the more outrageous or absurd the situations in the film become, the more the whole thing - from the quietest of conversations to the sight of the son, bathing in his mother's seemingly endless river of lactation - begins to make sense.

If the film is shocking or grotesque, it is a deliberate effort on the part of the Miike to show the extent of the decline of their society as the filmmakers see it. By taking these characters to the furthest possible extreme, beyond the merely dysfunctional, Miike and his collaborators seem to be making a deliberate comment on the level of absurdity and horror to which the situation within the family unit has transformed.

In many respects, this is Miike, as filmmaker, working in much the same way as the eponymous Visitor; offering a wakeup call to his characters and his audience in an attempt to stir a reaction. He isn't simply standing back, like Kiyoshi, observing with his video camera as the home fires burn (figuratively) to the ground, but is instead taking an active part in the disintegration; documenting with glee the fall from grace of these characters as they slide into outright insanity, though never once questioning their actions or passing comment until the very end. It is only then, after they've gone beyond all reason that they can step back and look at themselves in a new light, to see what they've become.

If these scenes of rape, domestic abuse and general degradation might lead some to fall back on the well worn criticism that Miike is a vicious misogynist, it is important to remember that the unification and eventual rebirth of the family into a happy, well-functioning unit, comes not from the stranger in the leather trousers and Hawaiian shirt, but from the wounded mother; the symbol of Japanese modernity: the form from which each of us are born. It is only at the end of the film, in which the father and daughter, draped in sheets of glistening blue plastic, suckle the breast as mother floats on a cosmic-calm of post-coital serenity that the order is finally restored.

These sequences, which can be seen as empty provocation if we buy into the image of Miike as the sadistic wildman of films like Dead or Alive (1999) and Ichi the Killer (Koroshiya 1, 2001) - and not the intelligent, socially-aware filmmaker of The Bird People in China (Chûgoku no chôjin, 1998) and his two "Young Thugs" movies, Innocent Blood (Chikemuri junjō-hen, 1997) and Nostalgia (Bōkyō, 1998) - always serve a purpose within the narrative. The disgrace of the father, exaggerated in the worst possible way, makes him unable to offer a model for his disconnected teenage son; a boy who takes the vile abuse of his bullies and turns it against his mother - herself, a hopeless, heavily in-denial heroin addict who has turned to the murky-world of prostitution in order to feed her addiction. Without the model of domestic stability in place the daughter has gone AWOL, finding affection from a succession of lecherous strangers with no way of return. And of course, if the only way that she can find love and tenderness from her own father is in seducing (and eventually mocking his lack of prowess), then that's the obvious extreme that she's been pushed to.

Nonetheless, the real power of Visitor Q is not in its scenes of spectacle and provocation, but in the odd moments of transcendent beauty that are formed from the most improbable presentation of events. For example, a single reaction shot of Keiko, the mother, coming home to an empty dinner-table, tells us all we need to know about this character - her hopes and disappointments - as the absence of the family that once existed in some form of unity is now spiralling out into the cosmos. Similarly, the closing scene, which captures the reaction of Miki as she discovers the unification between mother and father as if emerging from some kind of somnambulist-like trance - again, viewed telling through the rectangular frame of a window - as the music swells and the camera drifts ever forward to a moment of potential reconciliation.

Although it is filled with exaggerated, over-the-top farce and a mocking humour, the film also possesses this more personal quality, explicit in the fearless performances of the cast and the sheer jaw-dropping ethereal grandeur of its closing scene.

One of the most interesting developments to occur in contemporary cinema over the course of the last ten years has been the increase in availability of digital filmmaking technology and the obvious benefit that this has offered to filmmakers, not least in terms of reducing budgets and production schedules, but in looking at the world from a new perspective. From Lars von Trier's The Idiots (Idioterne, 1998) to David Lynch's Inland Empire (2006), the look and more importantly the feel of digital photography has further obscured the recognisable line between drama (i.e. artifice: the filming of a performance within a carefully constructed frame) and reality. The "look", as it were, is closer to a perceived realism as presented by that of reality television, docudrama or a fly on the wall; the sense that we are seeing something closer to reality because the sparseness of its images, the relaxed nature of its performances and the awkward passages usually removed or tightened by the editing process remind us of the unrehearsed spontaneity of everyday life.

The feel of digital cinema (discounting the more pioneering digital work of films like Attack of the Clones (2002) or Zodiac (2007), in which the attempt is to make digital look as glossy and well-defined as 35mm celluloid) is the stuff of wedding videos or the filmed performances of a high school musical. The effect is more recognisable to our own (non-professional?) experiments with filmmaking in the domestic sense; something that worked in favour of a film like Thomas Vinterberg's masterful Dogme95 experiment Festen (The Celebration, 1997), in which the appearance of a self-shot family portrait plays on the idea of documenting family celebrations in order to preserve that particular memory or occasion. By adopting this specific style, the filmmaker is able to make convincing those scenes that may have previously overwhelmed us, or become an obstruction as a result of their melodramatic superfluities.

Would an audience have believed Christian's (Ulrich Thomsen) fraught dinnertime speech delivered to his father (Henning Moritzen) or the anxious quaver of desperation as he revealed the tragic back-story of his suicidal twin-sister to a room-full of dumbfounded relatives and guests in Vinterberg's aforementioned magnum-opus if it had been shot with all the beauty and grace of a Merchant-Ivory production? Or does the recognisable candid-camera-like intrusion that digital video presents create a more reasonable window into the world in which the exaggerated melodrama of the plot becomes almost plausible?

Visitor Q directed by Takashi Miike, 2001:

Festen directed by Thomas Vinterberg, 1998:

The Remains of the Day directed by James Ivory, 1993:

Festen directed by Thomas Vinterberg, 1998:

The Remains of the Day directed by James Ivory, 1993:

The use of video implies "realism", but only because of these associations and the natural shock of seeing images stripped of their usual cinematic-gloss. However, it also possesses a more powerful contrast; with the actual look of video, in comparison to 35mm film (or even Super8 or 16mm film) actually becoming more abstract and surreal in both texture and appearance. Although we might identify something apparently truthful (i.e. recognisable) in the presentation of these digital pictures, there is also that alien quality, which exaggerates and distorts.

This particular contrast works perfectly in director Takashi Miike's gloriously subversive satire, Visitor Q (Bijitā Kyū, 2001); a film in which the required use of digital video actually shapes, not only the look and feel of the film, but the actual development of its narrative. The film, best described as a chaotic snapshot of contemporary middle-class Japanese domesticity, is essentially a demented pastiche of the Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini's classic psychological drama, Teorema (1968); a film in which the notion of a seductive young corruptor of innocence - as personified in that particular film by a calculated Terrance Stamp - is here turned upside down; with Miike and his screenwriter Itaru Era turning a stifled, claustrophobic investigation into the unspoken psychosexual desires of a family of Italian intellectuals into a slapstick farce of animated subtleties and stark, almost Buñuelian satirical intentions.

Teorema directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1968:

Visitor Q directed by Takashi Miike, 2001:

Teorema directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1968:

Visitor Q directed by Takashi Miike, 2001:

Visitor Q directed by Takashi Miike, 2001:

Teorema directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1968:

Visitor Q directed by Takashi Miike, 2001:

In both films the plot could be described in a single-line; "A stranger is accepted into a normal family and becomes a catalyst for radical change." As the critic Chris Campion notes in his short-essay included with the Tartan Video Region 2 DVD release of the film, "Pasolini's movie can be seen as both a political and religious allegory; the disintegration of the nuclear family symbolising the rejection of bourgeois values."

In Visitor Q, this initial set-up is turned inside out. In the Pasolini film, the change is for the worse, and the tone of the movie is bleak and filled with deception. However, in Miike's film, the change is for the better, and although this is a picture filled with violence and brutality, the tone is ultimately hopeful. You can feel it in the warm swell of Kôji Endô's subtle score as it lifts the scenes at disarming moments throughout; turning the flashes of degradation and dismemberment into acts of tender mercies.

In Miike's film, the wandering stranger, played here by the actor and director Kazushi Watanabe, positions himself at the heart of the Yamazaki household, where the family, consisting of father Kiyoshi (Kenichi Endo), mother Keiko (Shungiku Uchida), daughter Miki (Reiko Matsuo, billed here as 'Fujiko') and son Takuya (Jun Mutô) are on the precipice of absolute chaos. The lingering air of apocalyptic dread, dysfunction, disorder and disarray is established in the very first scene, with the character of Miki boldly asking the question on-camera, but also to-camera (and by extension, questioning the natural voyeurism of the cinema and the home-cinema audience) - "You wanna know the truth about the youth of today... to predict the future of Japan... this hopeless future?" Miike's provocative inter-title, which then audaciously asks "have you ever done it with your dad?" establishes the dominant tone of the film, finding the middle-ground between absurd parody and actual documentary; polemic and pastiche.

Beyond the more immediate display of the film's humour and approach, Visitor Q demonstrates a keen awareness of the various societal concerns and issues currently facing the modern Japan. It touches on all the major issues, including sexual abuse, prostitution, drug-dependency, schoolyard bullying and the gradual erosion of the archetypical family unit, in which father and mother are no longer in a position to fulfil the basic requirements of the patriarch/matriarch model of maintaining an efficient, well-functioning household.

It is not simply a work of empty shock or spectacle (although it can - no doubt - be approached on such a level), but rather a film that should be appreciated and experienced as a serious commentary on the cycle of violence as illustrated by a family in which the roles of the father and mother have become debased and obscured. A world in which the father is a disgraced news reporter exploiting the decline of his family as way to claw back a sense of respect from his associates and peers, and where the mother has become a tortured heroin addict, turning tricks in order to fund a habit that allows an escape from the regular beatings of her wayward teenage son.

The film implicates the failure of the parents in the failure of their children; for instance, the father's emasculation/humiliation at the hands of a gang of teenage hoodlums' gives way to the son's own torment from the ritualistic abuse of his classmates. This in turn is expressed through his own violent attacks on his mother, who now finds solace in the needle, or in the loveless embrace of anonymous sex-starved salary men, and the obvious parallels here with her own daughter, lost in the big city and also selling sex, until the cycle of failure and abuse, as it is passed back and forth between the generations, becomes painfully clear.

We can see similar issues presented in other Japanese films released around the same period as Miike's film, including the director's own off-the-wall musical satire The Happiness of the Katakuris (Katakuri-ke no kōfuku, 2001), in which the notion of the family in the traditional sense is again documented with a perverse and darkly comic approach that obscures the underlining seriousness of its message. Added to this a film like Shinya Tsukamoto's blistering Bullet Ballet (1998), in which the growing divide between the generations and the punishing loneliness of middle-class Japanese existence is projected against a plot that riffs on Taxi Driver (1976) and Neil Jordan's Mona Lisa (1986); as the characters find escape in nihilistic violence and self-punishment to awake them from the numbing slumber of everyday life.

Such concerns are also very much apparent in the J-horror movement of the late 1990s and early 2000s, as films like Ring (1998) and Pulse (Kairo, 2001) depict the growing disconnection between a generation who find comfort in technology; consigned to a world in which even our ghosts are forced to wander the streets in a lonesome, never-ending limbo. The issues facing the youth of Japan, as alluded to by the presentation of the son, Takuya, are also documented in Shunji Iwai's great film, All About Lily Chou-Chou (Rirī Shushu no Subete, 2001); another picture that uses digital video to abstract the presentation of the world but to also create a vague association with reality.

If Miike's use of video abstracts the presentation, then the line between the viewer and the viewed is further obscured by the position of the lead character, who himself is seen documenting the proceedings with his own pocket-video camera; creating an odd sense of confusion as the story literally consumes itself. The footage shot by the character is as much a part of the film as the footage shot by Miike's frequent cinematographer Hideo Yamamoto, with the distinction between the two forms creating a further blurring of perspectives, as we are forced to question if the strange shifts into more abstract or fantastical moments of surreal expression are real or simply symbolic.

As the writer Tom Mes suggests in his book Agitator: The Films of Takashi Miike (FAB Press, 2003), the shifts in the narrative and the construction of these characters are nothing less than allegorical. Although it all seems incredibly haphazard and thrown together with a complete disregard for convention, there is a strange kind of logic at work in which the more outrageous or absurd the situations in the film become, the more the whole thing - from the quietest of conversations to the sight of the son, bathing in his mother's seemingly endless river of lactation - begins to make sense.

If the film is shocking or grotesque, it is a deliberate effort on the part of the Miike to show the extent of the decline of their society as the filmmakers see it. By taking these characters to the furthest possible extreme, beyond the merely dysfunctional, Miike and his collaborators seem to be making a deliberate comment on the level of absurdity and horror to which the situation within the family unit has transformed.

In many respects, this is Miike, as filmmaker, working in much the same way as the eponymous Visitor; offering a wakeup call to his characters and his audience in an attempt to stir a reaction. He isn't simply standing back, like Kiyoshi, observing with his video camera as the home fires burn (figuratively) to the ground, but is instead taking an active part in the disintegration; documenting with glee the fall from grace of these characters as they slide into outright insanity, though never once questioning their actions or passing comment until the very end. It is only then, after they've gone beyond all reason that they can step back and look at themselves in a new light, to see what they've become.

If these scenes of rape, domestic abuse and general degradation might lead some to fall back on the well worn criticism that Miike is a vicious misogynist, it is important to remember that the unification and eventual rebirth of the family into a happy, well-functioning unit, comes not from the stranger in the leather trousers and Hawaiian shirt, but from the wounded mother; the symbol of Japanese modernity: the form from which each of us are born. It is only at the end of the film, in which the father and daughter, draped in sheets of glistening blue plastic, suckle the breast as mother floats on a cosmic-calm of post-coital serenity that the order is finally restored.

These sequences, which can be seen as empty provocation if we buy into the image of Miike as the sadistic wildman of films like Dead or Alive (1999) and Ichi the Killer (Koroshiya 1, 2001) - and not the intelligent, socially-aware filmmaker of The Bird People in China (Chûgoku no chôjin, 1998) and his two "Young Thugs" movies, Innocent Blood (Chikemuri junjō-hen, 1997) and Nostalgia (Bōkyō, 1998) - always serve a purpose within the narrative. The disgrace of the father, exaggerated in the worst possible way, makes him unable to offer a model for his disconnected teenage son; a boy who takes the vile abuse of his bullies and turns it against his mother - herself, a hopeless, heavily in-denial heroin addict who has turned to the murky-world of prostitution in order to feed her addiction. Without the model of domestic stability in place the daughter has gone AWOL, finding affection from a succession of lecherous strangers with no way of return. And of course, if the only way that she can find love and tenderness from her own father is in seducing (and eventually mocking his lack of prowess), then that's the obvious extreme that she's been pushed to.

Nonetheless, the real power of Visitor Q is not in its scenes of spectacle and provocation, but in the odd moments of transcendent beauty that are formed from the most improbable presentation of events. For example, a single reaction shot of Keiko, the mother, coming home to an empty dinner-table, tells us all we need to know about this character - her hopes and disappointments - as the absence of the family that once existed in some form of unity is now spiralling out into the cosmos. Similarly, the closing scene, which captures the reaction of Miki as she discovers the unification between mother and father as if emerging from some kind of somnambulist-like trance - again, viewed telling through the rectangular frame of a window - as the music swells and the camera drifts ever forward to a moment of potential reconciliation.

Although it is filled with exaggerated, over-the-top farce and a mocking humour, the film also possesses this more personal quality, explicit in the fearless performances of the cast and the sheer jaw-dropping ethereal grandeur of its closing scene.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Schalcken the Painter (1979)

Schalcken the Painter [Schalcken the Painter [Leslie Megahey, 1979]: This is a film I first saw around four years ago. At the time I found...

-

Schalcken the Painter [Schalcken the Painter [Leslie Megahey, 1979]: This is a film I first saw around four years ago. At the time I found...

-

In discussing the brief snippet from the ever contentious Uwe Boll's no-doubt harrowing new film Auschwitz (2011) - particularly the way...

-

The Image of Happiness or: 'the black leader' "The first image he told me about was of three children on a road in Icel...